Data Literacy Through Time

An urgent call to action after an 100 years of inaction on data skill has brought us to crisis point.

Elements of the data skills gap were predicted over one hundred years ago. Yet, the data skills gap has grown to the point that reskilling programmes of a historic scale are needed to prevent an employment crisis.

This article gives a brief history of the data skills gap to explain why the article's opening line is not an exaggeration and to suggest a way forward.

1900-1950s - Correct prediction on need for statistical skills

In HG Wells's 1903 book "Mankind in the Making" he predicted the time would come when it would be

"as necessary to be able to compute, to think in averages and maxima and minima, as it is now to be able to read and write."

HG Wells saw the increasing use of data and statistics in financial, social and political discussions and concluded that without a level of statistical awareness, people would not be able to keep up with current affairs debates and would become easy targets for manipulation.

Almost fifty years later, Darrell Huff showed that this risk had become a reality. In "How to lie with statistics", he described eight ways that by 1954 advertisers, politicians, and others were using statistics and aggregations to mislead. In his view

"the secret language of statistics, so appealing in a fact minded culture, is employed to sensationalise, inflate, confuse and oversimplify. Statistical methods and statistical terms are necessary ... but without writers who use the words with honesty and understanding and readers who know what they mean, the results can only be semantic nonsense."

These views and his book are as relevant today as in 1954.

Whilst HG Wells's suggestions on statistical skills would not have helped with dishonest writers, it would have helped to create informed readers.

At this point, there was a skills gap problem, but misleading statistics were not creating a crisis.

1980-2010s - Correct prediction on need for data literacy

As computing became more widely used, alarm bells were raised again, this time around the risks from the increased use of databases and reporting. In 1988 Data Processing Digest made the case that

"users need education in appropriate uses of data and the risks of misuse. The ease of asking "what if" can lead to an outpouring of reports that mean little or, worse, are filled with errors. Education in "data literacy" would address this."

If, like me, you've spent time in corporate environments drowning in different reports, you will know that this prediction also came true.

This also illustrates the growing technical skills needs from a need for statistical awareness in the 1950s to basic data literacy in the 1980s.

At this point, users are just consumers of reports and therefore, data literacy includes the knowledge to ask questions about provenance (where did the data come from, what version was used etc.), reliability (have the calculations been reviewed, the data been reconciled back to a trusted source etc.) and appropriate use (who owns the data, what regulations apply to its use) of data.

The skills gap also grew from the cost of people being misled to the cost of data errors. Famous examples of the cost of data errors include:

Nasa losing a $125m Mars orbiter because some teams worked in metric units and others in imperial units;

Barclays accidentally buying 127 contracts with a negative value from Lehman Brothers due to a mistake filtering rows in Excel; and

H&M incurring a €35m fine after accidentally sharing personal data records to everyone in their company.

More recently, low and no-code data tools have made data work and complex analysis more accessible. This has brought huge benefits, but it has also raised the bar for data skills again, as a large percentage of people are now expected to have the skills to query and merge data sets and to understand the limitations and appropriate use of predictive algorithms and tooling.

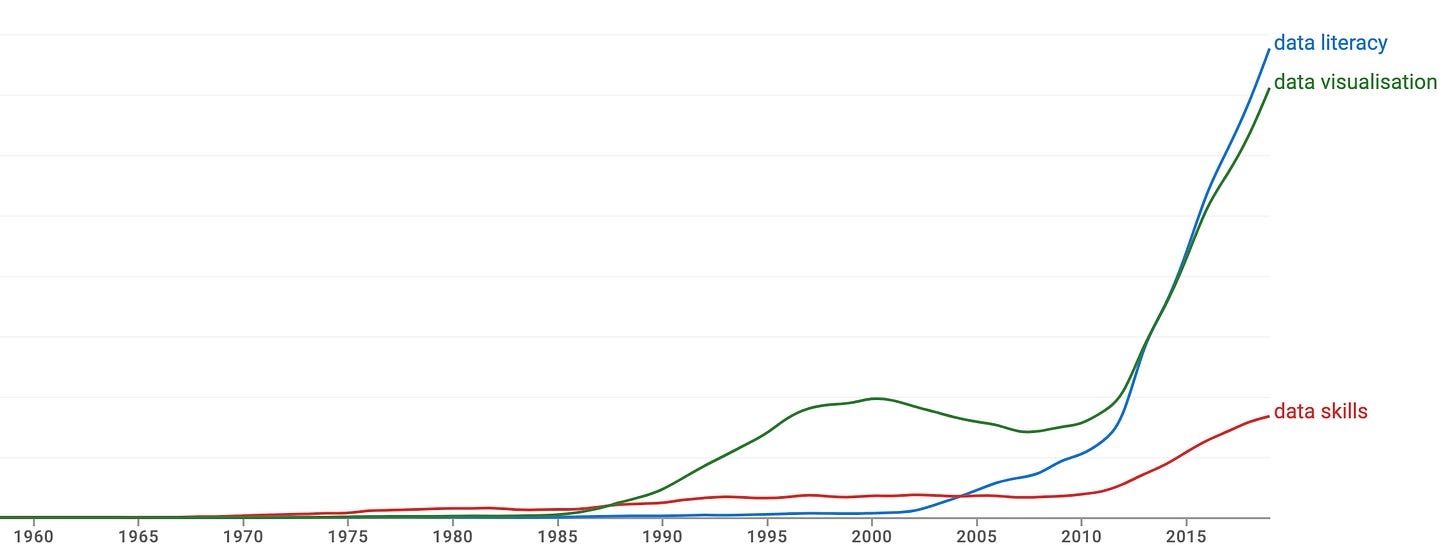

It's no surprise that the self-serve data tooling companies and their communities have become the most prominent data literacy advocates. As the Google Ngram of word frequencies shows, the uptake of data visualisation tooling was quickly followed by an increased discussion on data literacy.

In short, the 1980s prediction on the need for Data Literacy skills to avoid costly data errors and the proliferation of meaningless reports proved correct.

The data skills requirement for the average knowledge worker had multiplied to include several technical subjects. It's not yet a crisis, but the cost of the data skills gap is sizeable.

2020-2030s? - Predictions on data skills and unemployment

The predictions now are that the widespread adoption of robotic automation tools, machine learning tools and AI tools will lead to long-term unemployment issues unless we improve the level of data and technical skills in society.

In short, this third prediction describes an even bigger skills gap and a crisis.

Should we believe this prediction just because two earlier predictions were correct?

Of course not.

For one, it is easy to look back in the past, find the handful of correct predictions and ignore all the predictions (like flying cars) that didn't come true.

So let's make the argument for a crisis in a different way.

So far, society and businesses, in particular, have been so slow to adopt existing data tools. The most used tool by the average knowledge worker is still the spreadsheet, a technology first released in 1979, the same year as the first Sony Walkman.

Since spreadsheets, many technologies have been released that would improve the productivity of all knowledge workers and deliver significant returns to businesses. I know this from the experience of seeing eight-figure returns from an enterprise-wide Tableau rollout, and other technologies would give similar benefits.

However, only a few companies have invested in tooling or skills training for all their knowledge workers. In fact, the only reason why every knowledge worker has access to spreadsheets is that they were part of a productivity package along with a word processor and email manager. Companies never made a conscious decision to invest in data tools or technical skills for their knowledge workers.

As a result, not only is the spreadsheet the most commonly used office tool, but many office workers' technical skills have never progressed beyond working in spreadsheets.

We, therefore, find ourselves in a situation where many people's skills relate to technologies that are 40 years old at the same time as technologies like RPA and generative AI are starting to compete for their jobs.

For those whose skills are up to date, breakthroughs like ChatGPT and DALL-E are less of a surprise and less of a threat. Many people see the opportunity not only to use these tools to become more productive but even to use their proprietary data sets to give themselves a cutting edge. For example, designers can use unpublished works and draft designs to train a generative AI tool on their style.

By contrast, new technology is increasingly a mysterious, opaque threat if you've only ever worked in 40-year-old tech like spreadsheets. The skills gap between your current work and new technology is becoming overwhelming.

This is why we are now at a crisis point, and unless we intervene soon, we risk creating structural unemployment at a scale that hasn't been seen since the mass closure of shipyards and mines.

Signs of hope and next steps

There are, however, signs of hope and clear next steps to avert a crisis. The EdTech sector is booming and is forecast to grow at an annual rate of 16.5% a year. The market has noticed this trend.

Businesses now have a moral duty to invest in reskilling their knowledge workers.

Many companies say they follow a cloud-first strategy because digital natives have shown the benefits. Digital natives also have a different skills mix in their workforce.

It is time for companies to spend more money on reskilling programmes than on technology infrastructure or trying to hire, rather than build, the skills they need.

Again there are positive signs here. When, in 2016, I made a case for a data analytics graduate programme at JLR, I couldn't find many other corporate data graduate programmes to learn from. Now most large companies have data graduate programmes.

However, universities are slower to change. I perceived a drop in technical skills levels from final-year students between 2016 and 2022. Industry can help by defining a common skills framework that universities can work with.

The breakthrough in AI and technology, in general, is hugely exciting and represents opportunities rather than threats as long as we invest in developing the right skills in society.